Lifting the Curtain: Former U.S. Visa Officer Düden Freeman on What Really Happens at the Window

A Diplomat’s Path to the Visa Window

For many, the U.S. visa process is an enigma, an opaque system where life-altering decisions are made in minutes. For Düden Freeman, the decision to launch Idelire Consulting and its educational platform Visas 101 to help visa applicants better understand the U.S. visa process felt not only her professional responsibility but also a deeply personal journey.

Freeman became a U.S. diplomat in 2012 after navigating a year-long selection process to join the State Department’s foreign service. Her postings took her across the globe, from Mali to Spain, then from Malaysia to the Atlanta Passport Agency. It was in Madrid, during her second tour, that she stepped into the role that would shape her future: consular officer.

“Every brand-new foreign service officer is essentially required to do a consular tour,” Freeman explains. “Mine was in Madrid, where I interviewed tens of thousands of foreigners for different kinds of visas, nonimmigrant, employment-based, family-based. Pretty much every letter in the alphabet soup of U.S. visa categories.”

The 240-Second Interview That Changes Lives

It was in those interview booths that Freeman saw how little applicants understood about the process. A typical visa interview lasts about four minutes, or 240 seconds. In that time, an applicant must convince a U.S. government official of their eligibility.

“Those 240 seconds could change your life for the rest of your life,” Freeman says. Yet most applicants, she noticed, arrived unprepared. They gave short answers, let the officer control the interview, and failed to articulate what made them qualified.

“You paid for that interview,” she stresses. “It does not guarantee approval, but it does give you the chance to advocate for yourself. If you go in completely clueless, the officer is likely to deny you.”

And for student visa applicants, with the recently implemented additional social media vetting process, preparation matters more than ever. “If an officer thinks you are qualified, they still have to deny you under section 221(g) of the INA so they can run checks,” Freeman explains. “That includes 20 minutes of reviewing your social media. But they only invest that time if you have already convinced them you qualify. If you go in unprepared, they will not.”

Dispelling the DS-160 Myth

Applicants often believe their fate is sealed before they even enter the consulate, that their answers on the DS-160 form determine the outcome. Freeman pushes back firmly.

“That is not true,” she says. “Yes, there are security-related questions where a ‘yes’ answer can raise red flags, such as crimes, drug trafficking, or prostitution. But even then, the officer still needs to talk to you. They have the Foreign Affairs Manual in front of them, and sometimes exceptions apply. Nothing makes you automatically ineligible without that conversation.”

In complex cases, officers may issue a temporary denial under section 221(g). “It is a denial that can be overcome,” Freeman explains. “It gives the visa officer time to decide whether the application leads to an issuance or a more permanent denial. Decisions are not made before speaking with you.”

The Weight of Past Denials

Visa denials, Freeman emphasizes, leave a lasting imprint. “Case notes never get deleted,” she says. “Even if one day you become a U.S. citizen, your immigration history remains in the system.”

If you are denied a B1/B2 tourist visa under section 214(b), reapplying a week later raises immediate questions. “The officer will think: someone with the same training as me already denied this person. What has changed in one week?” Freeman explains. Unless there is a clear change, such as new evidence, resolved miscommunication, or altered circumstances, the outcome is likely to be the same.

Switching visa categories does not mean you are protected from future denials. For example, someone who was previously denied a tourist visa might later apply for an H-1B. While H-1B visas are not subject to 214(b), other denial grounds could still apply. Prior actions in the U.S., such as overstaying an ESTA or a tourist visa, working without authorization, or a past DUI arrest, can resurface in the officer’s decision-making.

“Immigration law is complicated,” Freeman says plainly. “That is why preparation is critical.”

Should You Reapply Immediately or Wait?

The natural instinct after a denial is to reapply quickly, hoping for a different officer or a different outcome. Freeman cautions against this reflex.

“It really depends on the case,” she explains. “Sometimes the denial was due to miscommunication. In that situation, after unpacking what happened, reapplying might make sense. But if your circumstances have not changed, it is better to wait. Otherwise, you are likely to be denied again.”

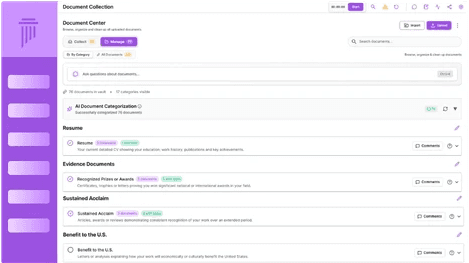

Part of Freeman’s current work involves this kind of “reverse engineering.” At Visas 101, former visa officers and consular managers review applicants’ DS-160 forms, walk through the interview as the client remembers it, and identify likely reasons for denial. “We make an educated guess about what went wrong,” she says. “Then we prepare the applicant to either reapply differently or wait until circumstances change.”

The Complex Case of the O-1 Visa

Startup founders often look to the O-1 visa after facing tourist visa denials. But even extraordinary ability visas are not immune from rejection.

“There is confusion about whether O-1 is dual intent like H-1B,” Freeman says. “It is not the same. An officer should never deny an H-1B under 214(b), but an O-1 can be denied under 214(b), even though dual intent is ‘permissible’ for O-1 visa applicants according to the Foreign Affairs Manual.”

Officers also have discretion to return an O-1 petition to USCIS for revocation if they believe it should not have been approved. “Today, more and more O-1s are being denied under 214(b),” Freeman notes. Sometimes, the reason is not qualifications but prior noncompliance. “I have seen an O-1 denied because the applicant did not follow the rules of their previous visa,” she explains.

The challenge for applicants is that officers rarely provide details. “They just hand you a letter saying you do not qualify under section 214(b),” Freeman says. “That is where we come in, to help applicants understand what might have happened.”

Why Attorneys Need Consular Expertise

For immigration attorneys, denials can be baffling, especially when petitions were approved by USCIS without requests for evidence. Freeman encourages attorneys to partner with former consular officers.

“Many attorneys do a wonderful job preparing visa packets and representing clients on paper,” she says. “But they cannot attend consular interviews. And I have seen visa applications with slam-dunk approved petitions get denied because the applicant was clueless about the interview.”

Mock interviews, Freeman argues, bridge this gap. “We can be blunt and objective in a way attorneys sometimes cannot,” she says. “We give feedback on body language, tone, word choice, the things that matter in those 240 seconds.”

When attorneys see their clients in mock interview sessions, Freeman adds, they realize how valuable this perspective is. “It is much better to get tough feedback from us before the actual interview than to face denial after months of work.”

Trends at the Window: More Scrutiny, Less Facilitation

Reflecting on recent years, Freeman sees a clear trend: increased scrutiny. “Applicants today are expected to be a lot better prepared,” she says. “Visa officers’ number one priority has always been protecting national security, but now it feels like that is overshadowing the other mission: facilitating legitimate travel.”

An Insider Who Knows Both Sides

What makes Freeman’s perspective unique is not just her years as an adjudicator but her own experience as an immigrant. “I have been a petitioner, I have been a visa applicant, I was a green card holder, and now I am a citizen who later served as a U.S. diplomat,” she says. “I know how nervous it feels to stand at that window, especially if English is not your first language.”

This dual perspective allows her to combine empathy with expertise. “It is a privilege to help people advocate for themselves,” she says. “Preparation does not erase nerves, but it gives applicants the confidence to tell their story clearly.”