From Tape Recorders to AI: Greg Siskind's Journey Building Immigration Law's Technological Future

The year was 1991, and Greg Siskind faced a problem that would have been unrecognizable to lawyers just a generation earlier and incomprehensible to those practicing today. Working at a large Nashville law firm, he needed to dictate documents into a tape recorder, deliver the tape to a word processing center with eight typists, and hope his work would eventually appear in his inbox. For a junior associate low on the totem pole, this system simply wasn't working.

His solution seemed extravagant at the time: spending $3,000 (equivalent to perhaps $8,000 or $9,000 today) on a personal computer. The goal was mundane: to do his own typing and take control of his workflow.

That decision would ultimately position Siskind at the forefront of legal technology for more than three decades, culminating in his current work developing Visalaw.ai, what he describes as the planet's largest immigration law library powered by artificial intelligence.

Greg Siskind's Early Career: When Immigration Law Saved a Legal Career

Siskind hadn't planned on staying in law at all. Starting his career in mergers and acquisitions at a large firm, he found the work unfulfilling and was actively planning to leave the profession for graduate school in another field. Then an immigration case landed on his desk.

"This is an area of law that I would stay in the profession if I can develop that," Siskind recalls thinking. But there was a significant obstacle: he was living in early-1990s Nashville, Tennessee, a city he describes as more of a "hillbilly town" focused on country music, not the cosmopolitan technology hub it has become today. Immigration work seemed impossible to build from such a location.

His then-girlfriend (now wife) made the stakes clear: she would support whatever he decided to do, but only if he stayed in Nashville. Relocating wasn't an option if they wanted to remain together.

How Technology Became Greg Siskind's Ticket to Immigration Practice

The same computer Siskind purchased to solve his typing problem came with something else: a modem. And that modem provided access to something called Usenet newsgroups, pre-web online bulletin boards where people gathered to discuss specific topics.

Siskind discovered immigration-focused newsgroups with messages from people asking questions. Notably absent from these digital spaces: lawyers. Most attorneys in the early 1990s didn't have computers, and even fewer had internet access.

"There were no lawyers to be found anywhere in these places because lawyers didn't have computers and didn't have Internet access," Siskind explains. "But I did have Internet access. I think I had it through CompuServe."

He began answering questions, connecting with tech workers and university employees (the only people who had internet access in 1990-1993). A realization struck him: immigration law is federal, cases are filed by mail, and he didn't need clients in Nashville. This new technology could be his ticket.

Greg Siskind and the Birth of Immigration Law Online

Then came 1993 and the Mosaic web browser, the first graphical interface that would evolve into everything we know about the internet today. Siskind recognized that the earliest websites belonged exactly to the clientele he was seeking: tech-savvy professionals who needed immigration services.

He spent six months building a website for his practice. In 1994, he gave notice to his law firm and launched his solo immigration practice with that website as its foundation. Thirty-one years later, that same website still serves as the cornerstone of his firm.

But the website was just the beginning. Technology continued to shape not just Siskind's marketing but his entire approach to legal practice.

The Challenges That Shaped Innovation in Immigration Practice

Beyond the typing and internet access challenges, early 1990s immigration practices presented obstacles that seem almost comical today. Immigration forms existed only on paper, with no copies accepted. Some included carbon copies. The INS office serving Nashville was in Memphis, 200 miles and three hours away.

"I would have to drive down to Memphis 200 miles to be able to pick up forms and bring them back," Siskind recalls. "There actually was sort of a black market as well from lawyers that would hoard forms and then sell them to other lawyers because they had access to them and you had a deadline."

Each technological advance (from email to document management to case management systems) represented not just convenience but the difference between a sustainable practice and an impossible one.

Expert Systems and AI: Greg Siskind's Early Experiments with Legal Automation

Around 2015, Siskind began experimenting with AI expert systems, elaborate decision trees that could produce documents or answers based on user inputs. Using platforms like Neotologic and later Afterpattern (acquired by NetDocuments to become PatternBuilder), his firm built increasingly sophisticated tools.

One of his first projects targeted DAPA, a program similar to DACA that would have provided relief to 4 million parents of American children. Working with the Neotologic platform, Siskind's team built applications in both English and Spanish, ready to launch the moment the Supreme Court issued its decision.

"We figured that if it didn't happen with the Supreme Court, then we would have gotten a good education on how to do the building tools out," Siskind explains. "And if it did, we would like basically flip the switch on this app like the moment the court issued its decision."

Though the Court disappointed them, the education proved invaluable. His firm continued building expert system applications for mass litigation, creating tools to generate declarations from potentially thousands of plaintiffs, developing H-1B public access file generators, and planning more elaborate applications like I-9 audit tools.

The Turning Point: When Greg Siskind Met Generative AI

Then came August 2022, and everything changed.

Siskind had been invited to speak on an AI panel at the American Bar Association Tech Show the following March. The organizers paired him with Pablo Arredondo from a company called Casetext. During their initial planning call, Arredondo asked Siskind about his AI background, then shared something remarkable.

"He was showing me a chatbot that looked very similar to what we would know with ChatGPT," Siskind recalls. "This was shortly before ChatGPT would change the world."

Arredondo explained that Casetext had early access to technology from a company called OpenAI, which would release something to the public in a couple of months. The tool Siskind was seeing ran on GPT-4, which wouldn't publicly launch until March 2023.

Casetext wanted to see how the technology worked in an immigration law firm. Most of their early partners were giant corporate firms doing very different work.

Building the Largest Immigration AI Library: Greg Siskind's Vision for Visa AI

Siskind began testing the Casetext tool and quickly identified a challenge: immigration lawyers don't primarily do case law research. They work with administrative materials, regulations, policy memos, and practice guides.

"Immigration lawyers are not really doing that much case law research," Siskind told Arredondo. But he had another idea: could they upload his own materials, including his massive "Cookbook," now a three-volume, 4,000-page reference work?

Arredondo agreed to let him experiment with his own content. "It was kind of like a crazy thing to be able to ask myself questions from my own books," Siskind reflects.

The experience revealed both the promise and the limitations of existing tools. For a couple of reasons, including a lack of immigration law content, Casetext was probably not going to work well for immigration lawyers, despite being a great product.

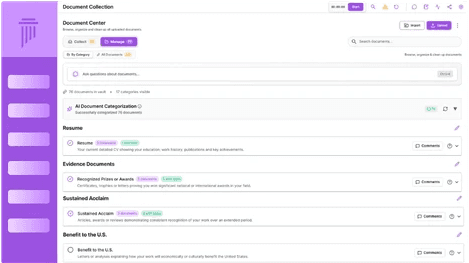

That realization led Siskind to develop what would become Visalaw.ai, powered by what he now describes as the largest immigration library on the planet.

Greg Siskind on Where AI Excels in Immigration Law Today

Reflecting on the current state of AI in immigration practice, Siskind sees clear areas of strength and continued challenges.

Legal research has reached impressive quality, particularly with the comprehensive library his platform has assembled and the availability of both GPT-4 and GPT-5 models for different use cases. The system provides citations, previews documents, and delivers reliable answers. This represents a dramatic improvement from just two years ago, when the technology was still in beta.

Drafting tools have also proven effective, though Siskind emphasizes the challenge of building quality drafting applications. Creating specialized tools for asylum applications, I-601 waivers, and other specific immigration forms requires significant subject matter expertise across multiple practice areas. Each tool demands constant updates as law and policy change, requiring lawyers to continuously review outputs.

The Future of Immigration AI: Custom Prompts and Agentic Systems

Siskind sees two particular areas of excitement for immigration law's technological future.

The first involves sophisticated custom prompting, using detailed, multi-page instructions to perform complex analytical tasks. He created a free website called Prompt.Law, initially designed as a teaching tool for law students, but applicable to practicing attorneys.

These prompts can handle complex tasks, such as analyzing Visa Bulletins against client priority dates. Early versions struggled with accuracy, getting perhaps 90% right, which isn't acceptable when relying on bad outputs can create problems for clients. But as models improved, particularly with better mathematical capabilities, these tasks became reliable.

"I think with prompt building, that's going to be a hot area because that allows law firms to make AI work for the things that are specific to an individual lawyer and law practice," Siskind explains.

The second frontier involves AI agents, interconnected systems that can handle sequential tasks throughout a case lifecycle. Imagine an initial phone call handled by AI, collecting information and scheduling consultations. The consultation itself might involve AI providing real-time feedback and spotting red flags. Afterward, the system could generate engagement letters, create matters in case management systems, set up bookkeeping entries, and send intake forms to clients.

"I'm talking about using AI all the way through your case till the end and then having all those systems interact where you don't have to have 12 different AI products," Siskind envisions.

Where Caution Remains: Greg Siskind's Warnings About Immigration AI

Despite his enthusiasm for AI's potential, Siskind remains clear-eyed about its limitations and the work required to make it function reliably in legal practice.

Building quality drafting tools requires not just technical capability but deep subject matter expertise and constant maintenance. Legal and policy changes demand immediate updates to templates and prompts. Law firms need lawyers continuously reviewing outputs to ensure quality.

The infrastructure requirements for effective AI use present another challenge. Firms need platforms that allow custom prompts, secure document uploads that protect client confidentiality, and access to strong underlying models. Many existing tools, including some from major technology companies, don't perform well for specialized legal tasks based on his experimentation.

Greg Siskind's Vision: Technology as Immigration Law's Continual Savior

Looking back across more than three decades, Siskind sees a consistent thread: technology has repeatedly solved problems that seemed insurmountable at the time.

That $3,000 computer in 1991 wasn't just about typing documents. It was about taking control of the workflow in a system that wasn't serving him. The modem wasn't just about internet access. It was about connecting with potential clients in a city that seemed too small for immigration practice. The website wasn't just about having an online presence. It was about fundamentally changing how legal services could be delivered across geographic boundaries.

Each technological advance (from blogging in 1998 to social media to expert systems to generative AI) has represented new possibilities for delivering better, faster, more accessible legal services.

"Technology can solve a lot of problems for me personally, like finding clients and being able to deliver services," Siskind reflects. "I've always been hunting for what new technology was coming out and how I can use it."

Today, as immigration law faces unprecedented complexity, processing delays, and access to justice challenges, Siskind's journey offers both inspiration and instruction. The tools have changed dramatically from tape recorders to AI-powered research platforms. But the fundamental insight remains constant: technology, thoughtfully applied with deep domain expertise, can transform how immigration law is practiced and who can access quality legal representation.

About Greg Siskind: Greg Siskind is an immigration attorney and technology pioneer who has been at the forefront of legal innovation for over three decades. He is the founder of Visa AI and author of the comprehensive Immigration Law Cookbook series. Siskind is a frequent speaker at legal technology conferences, including the American Bar Association Tech Show, and teaches as a guest lecturer at law schools on AI and legal technology topics. His firm pioneered the use of internet technology for immigration practice in 1994 and continues to lead in developing AI-powered tools for immigration lawyers.