From Nigeria to Florida: How Immigration Attorney Fola Olubunmi of Olubunmi Law Firm Built a Practice Rooted in Personal Experience

When Fola Olubunmi's sister discovered she was undocumented, her family was devastated, but with God on their side Fola and her sister strategized a path to legalization. For Olubunmi, who had studied law in England but put her legal career on hold after moving to America and starting a family, the crisis became a catalyst. She dusted off her law degree, took the bar exam, and jumped into immigration law with both feet.

"It was like, sink or swim," she recalls. "So I swam."

How Fola Olubunmi's International Background at Olubunmi Law Shapes Her Immigration Practice

Olubunmi's path to becoming an immigration attorney was anything but conventional. She studied law in England before relocating to the United States, where she met her husband and stepped away from practicing for 15 years. Her international background, which includes time spent in Belgium and Nigeria, gave her something that no textbook could provide: a deep understanding of the immigrant experience from multiple perspectives.

"When you've met with different people mixed with different cultures, I think you have a better understanding of humanity," Olubunmi explains. "And then you're just better equipped to deal with people."

This cultural fluency proves invaluable when working with clients from the African continent, South America, and other regions where perceptions of government and law operate differently than in the United States. Many of her clients come from countries with significant corruption, where legal systems function as obstacles rather than pathways. They arrive in America seeking economic opportunity without fully grasping the complexity of immigration law.

"The immigration laws here are so complex to begin with that a lot of people get here, become overwhelmed and hope everything will be fine," Olubunmi observes. "They stop actively working on legalizing their status."

Rather than judging her clients, Olubunmi focuses on education and strategy. Instead of judgement, she offers clarity. Instead of fear, strategy. Her work begins where her client’s understanding ends.

Why Fola Olubunmi Started Her Own Solo Immigration Law Practice

When Olubunmi decided to return to law, the choice to start her own firm was driven by something many working parents understand: the need for balance.

"Work-life balance is extremely important to me," she says. "And being available for my family was also extremely important to me. I wanted to go to games. I wanted to show up."

She knew that entering a traditional firm 15 years after law school would mean starting at the bottom, working 80-hour weeks doing grunt work. That wasn't compatible with her priorities as a mother. By launching her own practice, she gained control over her time.

But going solo required resources she didn't initially have. After passing the bar, Olubunmi turned to the American Bar Association's online community and simply introduced herself as a newly licensed attorney trying to figure out her next steps. Another Nigerian attorney saw her name, recognized a kindred spirit, and reached out.

"She was the one that encouraged me," Olubunmi remembers. "She said, you can do this. Just start your practice. If you have any questions, give me a call."

That mentor introduced Olubunmi to the American Immigration Lawyers Association, which became essential to building her practice. AILA provided resources on everything from automation tools to the substantive practice of immigration law itself. Olubunmi supplemented this formal education by sitting in on hearings at immigration courts, studying the cadence and craft of seasoned attorneys.

"I did a lot of studying, and then I would go to the immigration courts and just sit in on hearings just to get a feel for how it's done," she says. "It's a lot of work, and you have to put in the time, which I did."

How Olubunmi Law Handles Complex RFE Responses, Denials, and Immigration Waivers

Today, Olubunmi Law handles both family-based and employment-based immigration. But over the years, Olubunmi Law developed a niche: the cases that had gone off-track. Requests for evidence. Denials. Waivers. Appeals. The puzzles that required reconstruction rather than routine processing.

"That's been the bread and butter of my firm," Olubunmi explains. "Not just the affirmative applications, but assisting people that have already been in the process, either some were pro se and some had counsel and things went sideways."

These remediation cases require a particular kind of legal thinking. As denials rise and adjudication grows increasingly inconsistent, these cases demand a kind of legal forensics: identifying the flaw, restoring the narrative, building the argument that turns a no into a yes.

The current immigration landscape has made this work both more challenging and more necessary. Unique from most areas of the law, proceedings under the immigration laws of the United States include a high human cost,”the consequences of an immigration violation can fracture a family’s entire foundation, leaving devastation that ripples through every aspect of their lives”. Olubunmi reports seeing increased denials across the board, along with growing inconsistency in how cases are adjudicated.

"We're also seeing USCIS more involved in enforcement, which is something that is new," she notes. "That was up to CBP and ICE, but now we're seeing USCIS also being very involved in enforcement. And that's something that I just hadn't seen before."

Inside a Five-Year Immigration Battle: Fola Olubunmi's Most Challenging Case

One case illustrates both the complexity of immigration law and the persistence required to navigate it successfully. Early in her career, Olubunmi took on a client who had lived in the United States for over 40 years, believing she was an American citizen. The woman had been brought to the country at age two and raised with a fraudulent birth certificate her parents had obtained.

This client was completely unaware of her situation until a divorce and name change post 9/11 sent her to the DMV, where she was asked to obtain a better copy of her birth certificate. Upon reaching out to the vital records office- she was advised there was no record of her birth. She went to her mother to further inquire, only to be told she was not born in the United States and had been using a fake birth certificate.

The complications were staggering. The client had worked in law enforcement. She had voted in elections. She had held herself out as a U.S. citizen for decades, not knowing she wasn't one. In immigration terms, these were potentially fatal obstacles to legalization.

"All of these things can be the kiss of death in immigration," Olubunmi says. "She had held herself out to be a U.S. citizen."

The challenge was staggering: no lawful admission to adjust status, no documentation from childhood, and conduct that could legally bar relief forever. But the truth was on her side—she had never knowingly misrepresented herself.

But proving lawful admission, which is required for adjusting status within the United States, was impossible since she had been carried across the border as a toddler with no documentation. Olubunmi tried multiple approaches. She filed for adjustment of status using legal arguments that USCIS ultimately rejected after multiple interviews.

Then came a radical decision. Olubunmi recommended that USCIS place her client in removal proceedings, a suggestion that might seem counterintuitive but opened up a new avenue: non lpr cancellation of removal.

The immigration court found in their favor, but no visas were available in the relevant category. The case was administratively closed. Olubunmi filed a waiver for unlawful presence, which was approved. They prepared to process the visa at a consulate in Mexico, a country the client had never visited.

Then COVID-19 hit, freezing international movement.

When travel resumed, Olubunmi pivoted again. The client's son served in the military, making her potentially eligible for military parole in place. But when they filed that application, USCIS took a contradictory position: they had previously argued the client lacked admission for adjustment purposes, but now claimed she had been admitted, making her ineligible for parole in place.

"I essentially had to argue: no, you can't have it both ways. Pick a lane," Olubunmi recalls.

After nearly a year of additional delays, the parole in place was finally approved. The client finally received her green card-more than five years after the journey began.

"She finally got her green card this year after a fight of over five years with USCIS," Olubunmi says. "But that's one of many war stories."

The case crystallized something Olubunmi feels strongly about: the need for immigration reform. Her client was brought to America as a two-year-old. She had no knowledge of her status. She had built an entire life believing she was American. Yet legalizing her took half a decade of complex legal maneuvering.

"For somebody like that, if you didn't have competent counsel, she'd be deported to a country she's never been to, doesn't know anything about, doesn't speak the language," Olubunmi reflects. "There's got to be a better way."

Fola Olubunmi on AI in Immigration Law: Opportunities and Risks for Attorneys

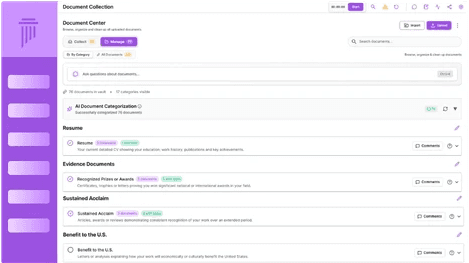

Like many attorneys, Olubunmi is navigating the emergence of artificial intelligence in legal practice. She uses AI tools but describes herself as "still very old school" in her approach.

Her primary concern isn't about AI replacing attorneys. It's about clients using AI without understanding its limitations.

"A lot of people are using artificial intelligence more and not recognizing that there can be errors," she says. "If you just take it and use it and then you take it as gospel, that can be dangerous."

Immigration law is particularly susceptible to AI missteps because it's so nuanced. Small details that might seem insignificant can determine whether a case succeeds or fails. Generic AI advice, even when technically accurate, may miss the specific circumstances that matter in an individual case.

"The devil is often in the details," Olubunmi explains. "It's easy to run into trouble if you're relying on artificial intelligence blindly."

When she does use AI in her own practice, she follows up with extensive verification. "I'm still going back and double checking and triple checking," she says. "So it's like, well, do I want to use it or just kind of do what I do?"

Fola Olubunmi's Advice for Immigrants Navigating Today's Immigration Climate

For foreign nationals currently on their immigration journey, Olubunmi has one overriding message: seek competent counsel now.

"Right now we're finding people are going out in the morning to go to work and then they don't come back home," she says, referencing increased enforcement activity.

Even if an attorney determines there are no current options for legalization, that consultation serves a purpose. It helps individuals understand their situation and prepare- for opportunities, for emergencies, for protection.

"Don't just stick your head in the sand," Olubunmi advises. "That's not working anymore."

She also warns against using notarios, non-attorneys who prepare immigration forms,whose errors often leave clients in worse shape than when they began. "A lot of people feel like immigration is simply filling out forms. It's not," she emphasizes. "Unless you have a completely clean slate and straightforward case, and even then a technical mistake can cause issues." I have had clients that were put in immigration proceedings because of "miscommunication and/or misunderstandings during their pro se interviews.

The path forward requires understanding your specific fact pattern and what options exist under current law. Good judges and adjudicators are still out there, Olubunmi says, but you can't take advantage of available relief if you don't know what your situation actually is.

For an attorney who entered immigration law because her sister needed help, the work remains deeply personal. Every case represents a person whose life hangs in the balance, who is trying to build something in America despite a system that often seems designed to stop them.

"Things are difficult," Olubunmi acknowledges. "But there are good judges out there, good adjudicators out there. You just have to know what your options are."