From International Arbitration to Immigration Law Practice in New York

When Sonal Sharma sat down to take the California bar exam in 2009, the chorus of doubt was deafening. As an attorney trained in India and practicing international arbitration in the Asia Pacific, she lacked the typical American law school credentials that most candidates carried into the examination room. Friends and colleagues were blunt in their assessments.

"Everybody told me, you're gonna fail. You don't have an education from the US," Sharma recalls. But armed with time and determination during a period when her H4 visa status prevented her from working, she made a decision that would alter the trajectory of her career. "I'm like, well, I don't have anything to do, so I'm just gonna do it."

She passed.

That moment of quiet triumph represented more than just a professional milestone. It captured the essence of an immigrant's journey, one defined by reinvention, resilience, and the refusal to accept limitations imposed by circumstances. Today, Sharma runs her own immigration law practice from her office on Broad Street in downtown New York, serving clients across business immigration categories while holding leadership positions with the American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA). Her path to this point was anything but linear.

Building a Career Across Continents: International Litigation and Arbitration Background

Immigration law was never part of Sharma's career plan. In fact, it wasn't even on her radar. Her early professional identity centered on international litigation and arbitration, a sophisticated practice area that took her from courtrooms in India to arbitration proceedings in Singapore.

"I was an international litigation and arbitration attorney. I practiced litigation and arbitration in India," Sharma explains. The work suited her analytical mind and appetite for complex disputes. When an opportunity emerged in Singapore, she relocated to join a boutique law firm specializing in marine arbitration disputes, immersing herself in the technical world of shipping conflicts and international commercial disagreements.

The move to Singapore represented her first experience as an immigrant navigating a new legal system and culture. She would need to start over, as her Indian qualifications didn't automatically translate to Singaporean practice. But the challenge seemed manageable, part of the natural progression of an ambitious legal career.

Then personal circumstances intervened. Her husband's move to the United States created a crossroads. Should she continue building her career in Asia, or follow him across the Pacific? The decision led her to America, setting in motion a series of events that would eventually reshape her entire professional identity.

The H4 Visa Challenge: Sonal Sharma's Personal Immigration Journey

Arriving in the United States on an H4 visa, Sharma encountered a frustration familiar to thousands of highly skilled professionals: the inability to work despite possessing significant qualifications and experience. The post-2008 economic crisis made the situation even more challenging. Companies weren't sponsoring visas, and her credentials, impressive as they were, carried no weight in a market where American law school degrees were the standard currency.

Rather than surrender to the waiting period, Sharma chose action. The California bar exam became her target, despite the skepticism from those around her. After passing, she found herself in an ironic position: a licensed attorney in California who still couldn't practice because of her visa status.

"Didn't work out still in terms of, like, job, because nobody was sponsoring visas. This was after 2008 crisis. So it was pretty bad until 2010, 2011," she remembers. The frustration mounted. She had proven her capability by passing the bar, yet doors remained closed.

Her response was to invest in further education. Sharma enrolled at NYU to pursue a master's degree in international litigation and arbitration, a strategic move that would allow her to transition from H4 to F1 status, ultimately providing work authorization through Optional Practical Training (OPT). The plan seemed solid, methodical, the kind of careful maneuvering that international professionals learn to navigate.

But even the best-laid plans can falter. After graduation, despite clearing the NY Bar Exam, opportunities in the United States remained elusive. So Sharma made what seemed like the logical next move: she returned to international arbitration, the field where she had built expertise and credibility.

Paris, London, and the Decision to Return: Global Legal Career Path

Sharma's resume began to read like a travelogue of global legal centers. She packed her bags and moved to Paris to work with Freshfields in their international arbitration group. The work was intellectually stimulating, and Paris offered the cultural richness that makes such relocations appealing to young professionals.

After her Paris stint, London beckoned. She joined WilmerHale's international arbitration practice, continuing to build her expertise in cross-border disputes. By any conventional measure, her career was thriving. She had worked in premier legal markets and built relationships with sophisticated clients facing complex international challenges.

But a fundamental question remained unanswered: Where was home?

"At that point, it was just like, decision to be made whether I want to be in Europe or I want to come back because my husband is here," Sharma reflects. The pull between professional opportunity and personal stability created tension. Her husband had established himself in a stable position in the United States. Moving him to Europe would mean both of them facing uncertainty again.

They chose stability over possibility. Sharma would return to America, to a legal market that had already rejected her multiple times. The decision carried risk. She had already taken the bar exam three times across different jurisdictions, reinventing herself repeatedly to meet local requirements.

"I was like, no, I think I'm done taking bar exams. Let's just go back. I think three are enough," she says with a laugh that suggests both exhaustion and determination.

Finding Immigration Law: How Sonal Sharma Discovered Her Calling

Timing, as they say, is everything. When Sharma returned to the United States, a policy change had finally granted her the ability to work. The H4EAD program, introduced during the Obama administration, provided work authorization for H4 visa holders whose spouses were on the path to permanent residence. For Sharma, it meant freedom to finally practice law in America.

Her entry into immigration law was almost accidental, born from personal frustration rather than professional ambition. Her husband's green card process had been handled by an attorney, but the experience left them both dissatisfied. "He kept telling me, you're a lawyer, and you have no idea what's going on with our case. What is this? I'm like, well, I don't know anything about it," Sharma recalls.

The gap between being a lawyer and understanding immigration law felt embarrassing. So when a position opened at an immigration law firm, Sharma applied with modest expectations. "I thought, let me just give it a three months and see. I just wanted to understand a little bit because of my husband's green card process."

Three months turned into five years. Then five years turned into a decade. "It's been 10 years. I didn't leave," she says. What began as a temporary learning experience evolved into a professional calling. The work combined legal complexity with human impact in ways that international arbitration disputes never had.

During those first five years at the firm, Sharma immersed herself completely. "I worked at a boutique firm for five years. And then five years ago, I just went on my own and opened my own law firm." The hours were grueling, often stretching to 14 or 16 hours per day, but they served a purpose. She was building expertise, understanding the intricate web of regulations, policies, and procedures that govern American immigration.

More importantly, she was building something else: the confidence that she could succeed on her own terms.

Launching a Solo Immigration Practice During COVID

The decision to start her own firm didn't come easily. For two years, her husband whispered encouragement mixed with challenge. "You need to go on your own. Why are you working for somebody else? You need to go."

Sharma resisted at first, comfortable with the security of firm employment even as she recognized that her future there might not align with her ambitions. "I didn't see my future there the way I wanted it to be," she admits. The question eventually became impossible to ignore: If not now, when?

The timing seemed absurd. It was peak COVID, a moment when most professionals were grateful simply to maintain their current positions. Starting a new business during a global pandemic contradicted every conventional wisdom about risk management. "I don't know what I'm doing, but let's go," Sharma remembers thinking.

But she had advantages that offset the timing risks. Five years of intensive practice had given her deep knowledge of immigration law. She had worked 14 and 16-hour days, learning not just the law but the practical realities of running cases. "I knew that I'm not going to change fields anymore. I'm gonna stick with immigration, and I was comfortable enough that, you know, five years I have worked hard, 14, 16 hours a day. I think I know my stuff, so I'm gonna be okay."

She was right. Five years later, her solo practice thrives, handling the full spectrum of business immigration cases: H1B visas, L1 transfers, PERM labor certifications, EB2 and EB3 employment-based green cards, EB1A extraordinary ability petitions, National Interest Waivers, O1 visas for individuals with extraordinary ability, TN visas, E3 visas, E2 and E1 treaty trader and investor visas. Approximately 10 to 15 percent of her practice consists of family-based immigration, typically connected to her business clients or referrals from existing relationships.

Looking back, Sharma sees the decision clearly. "Don't regret it. Should have done it sooner."

AILA Leadership: Chair of Asia Pacific Chapter and Board of Governors Role

For Sharma, professional success was never just about building a profitable practice. It required community, mentorship, and the institutional knowledge that comes from engagement with the broader immigration bar.

During her first five years in immigration law, AILA membership took a backseat. "I was not involved with AILA at all because I didn't have time. I was just working because I was managing a team of eight law graduates, attorneys, paralegals. I just had no time to for extracurricular activities out of my work."

But by her third or fourth year, she began attending New York chapter meetings, getting a sense of what the organization offered beyond her firm's walls. The annual conferences provided exposure to other practitioners, different approaches, fresh perspectives. Through AILA, she connected with prominent immigration attorneys like Cyrus Mehta, eventually contributing to his widely-read blog.

When Sharma launched her solo practice, AILA's importance intensified. "When I went on my own, that's when I started getting more involved because it was more important for me to have that support system, for my practice professionally and personally."

She became increasingly involved with the Asia Pacific chapter, a natural fit given her background and client base. "Most of my clients are from India and Asia region. So it makes sense for me to be associated with the chapter," she explains. She progressed through the leadership structure: committee member, secretary, vice chair, and finally chair, a position she has held for the past two years.

Sharma also co-chairs the Indian Subcontinent Interest Group and serves on the Department of Labor National Committee, given her substantial PERM practice. Perhaps most significantly, her role as chapter chair places her on AILA's Board of Governors, providing insight into how the association operates at the national level.

"That gives another perspective of how this large association operates and how the policy works and how we decide, you know, how we pick our battles in this administration," she reflects. Working alongside attorneys who have practiced for 30 or 40 years provides institutional knowledge that simply can't be acquired through individual experience alone.

Current Immigration Law Challenges: Attorney Burnout and Policy Uncertainty

Ask Sharma about the biggest challenges facing immigration attorneys today, and she doesn't hesitate. "The most important is the burnout for attorneys because there is just so much happening, there is just so much going on simultaneously that you're just putting out dumpster fires on a daily basis."

The stress hits solo practitioners and small firms especially hard. Large firms have resources, dedicated departments, support staff to distribute the workload. Solo practitioners like Sharma face a different reality. "At times one woman army, like doing everything that kind of takes away a lot of energy."

The constantly shifting policy landscape compounds the challenge. "On a daily basis, there is a new regulation coming up every day or every Friday," she notes. Keeping pace requires constant vigilance, and AILA's committee structure helps members stay current through rapid information dissemination.

For attorneys handling removal defense work, the challenges are even more acute, with detention issues adding urgent human stakes to already complex legal problems. The American Immigration Council (AIC) provides crucial support for this work, connecting attorneys with nonprofits serving vulnerable populations.

But perhaps the most existential challenge is the backlog and the deliberate policy choices designed to restrict immigration pathways. "It's going to get worse. So how do you navigate? Because it's going to have an impact on our practices as well."

Sharma acknowledges the reality bluntly. If H1B visas become impossible to secure, her practice would face serious challenges given her substantial H1B caseload. "I think we just have to be together in this and figure out a way how we are going to deal with this while keeping our sanity."

Immigration Technology and AI: Sonal Sharma's Perspective on Legal Tech Solutions

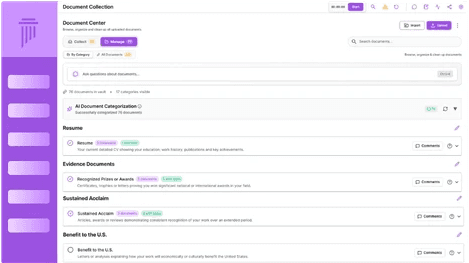

The rapid emergence of artificial intelligence in immigration law presents both opportunities and challenges. Sharma has tested multiple solutions, including platforms like CaseBlink and Parley for EB1 and National Interest Waiver cases, finding them helpful as starting points for paralegals building cases from scratch.

But she remains cautious about comprehensive solutions that promise to handle everything from customer relationship management to forms to drafting. "I have not found a solution that works very well for people like me, solo practitioners. I think it's very cost-prohibitive at this point."

The fundamental challenge, Sharma argues, isn't the technology itself but the integration of workflows. Questionnaires can be customized, and forms can be auto-populated, but if clients initially provide incorrect information, the automation creates more work rather than less. "You end up doing the same work that you would do by sending just a checklist."

She identifies a critical gap in current solutions: quality control at the right stage. "If it is like, okay, you send out a questionnaire, somebody reviews it, deals with the client, sends it back saying, this is missing. That is missing when it is complete, when we have done the quality check on that, this is complete, then the forms are filled out automatically or whatever, then that makes sense."

Until technology can solve that workflow problem, Sharma believes attorneys will continue to cobble together multiple tools rather than rely on single, comprehensive platforms.

Advice for Immigration Attorneys: Starting Your Own Firm

When aspiring solo practitioners ask Sharma for advice about starting their own firm, her answer is unequivocal: "Go for it."

She rejects the scarcity mindset that sometimes pervades the profession. "I think there is enough work for everyone. There are good people out there who are willing to help you."

The immigration bar, in her experience, operates on a pay-it-forward model. Attorneys who received help establishing their own practices offer guidance to the next generation. "Somebody reaches out to me, I help them out. Like, sure, why not? Go for it. I think there is enough space, enough work for everybody."

Competition exists, certainly, but Sharma sees it as validation rather than a threat. The market has room for different approaches, different specialties, and different service models.

The key is recognizing that being a solo practitioner means being more than just a lawyer. "You're just not a lawyer anymore. You need to think about marketing, you need to think about tech. You need to take care of everything." That multidimensional requirement can feel overwhelming, but it's also what makes solo practice rewarding for those who embrace the full scope of building a business.

Message to Immigrants: Sonal Sharma on Resilience and Opportunity in America

Having experienced immigration systems in Singapore, the UK, Paris, and the United States, Sharma brings a comparative perspective to questions about America's appeal for immigrants. Despite current challenges and policy uncertainties, she remains convinced that the United States offers something unique.

"I think anybody can achieve anything they want in this country. That, that's just the truth of it. It's not easy. It's tough. It can probably take as long as it took me, 18 years of my life. But you get your opportunity, and you definitely can achieve it."

Her own journey validates that belief. Multiple bar exams, visa struggles, geographic relocations, and starting over professionally three different times. But persistence created possibility.

For prospective immigrants, particularly students considering American education, Sharma offers practical counsel: do your homework. Understand what you're getting into, especially if taking significant loans to fund education. Policy changes can eliminate pathways quickly, so informed decision-making matters more than ever.

But for those with extraordinary credentials, she emphasizes that H1B visas aren't the only route. EB1 extraordinary ability petitions, O1 visas, and other pathways exist for those who qualify.

Her message ultimately returns to resilience. "It's not easy to leave your home and comfort zone and food and friends and family and everything to go to another place and start all over again. And I have done that three times."

The courage required for that journey, she believes, is itself predictive of success. Those willing to take that leap, to persevere through uncertainty and setbacks, typically find a way forward.

"Tough times never last," Sharma says, delivering the phrase with the conviction of someone who has tested it repeatedly. "Tough people do."

This article tells Sonal Sharma's story as a narrative of resilience and reinvention, showing how personal immigration struggles informed her professional expertise. The structure follows her journey chronologically while highlighting her current leadership role and practical wisdom for both attorneys and immigrants facing similar challenges.